we epitomise irony as we crave stability whilst doing all we can to undermine it, in some way

Arguably, next to food and love, money is the most existential thing of all. It helps us choose from a range of paths none of which are necessarily pre-set, while the line between suffering or not rests on its constant exchange. Of course, that links in directly to your sense of self as you negotiate the hierarchies around you. A winding and treacherous path at times where the directions switch from one moment to the next. What are you worth in the tick of an hour or the flicking of a gene, before you were born?

Well, it’s often said that to know where you’re going, it helps to know where you’ve come from. Sage advice it seems, but when it comes to being human: a tendency to repeat the worst of the past feels strangely inevitable. Whether, it’s government regulators failing to check on industries polluting the environment or selective amnesia and wilful blindness with respect to all areas of life: or safety officials ignoring the signs of an impending crisis for the sake of money or pride. We seem unwilling or unable to learn.

Lessons in anxiety are sitting there somewhere with questions over God, manhood or a hint of the judicial unanswered variably, depending on your carrier. Well, Kierkegaard asks: how much do we use evidence in our everyday lives when gambling can decide for us? It’s true, once, twice or thrice it may be, but we’ll keep the faith until we get what we need. Yet, what happens when the results are similar or exactly the same? A quote widely attributed to many including Einstein, says: ‘The definition of insanity is making the same mistake over and over, and expecting different results.’ Well, when it comes to money, folly is as fertile as the green in good grass as some of us are too stubborn to admit, while the paradox is sometimes stunning.

As the 20th Century saw humankind advance in areas like medicine and transport while later landing on the moon, it also saw around 187-million people killed in combat. In his 1993 book, ‘Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the Twenty-first Century’, Zbigniew Brzezinski, the retired National Security Advisor to former President Jimmy Carter estimated the lower range to be 167-175 million. So, conflict is a matter of fact, of course, as people and other animals compete for resources while of equal concern are the many short-term decisions, taken in the face of better options.

The 1920s in America, for example, saw a time of expanding wealth that many saw as infinite and as Harold Evans noted, in his book: ‘The American Century’:

‘The Great War, although hundreds of miles away in Europe, generated a boom in exports to lift the economy giving the average citizen an unprecedented shift in spending power. By its end, though, as exports fell, two recessions hit the economy before mass production and construction helped to find its feet again.’

Two years apart, the second recession, in 1920, emerged due to rocketing inflation fed by the still low-interest rates that had allowed for massive wartime productivity. In contrast, the gradual reduction in war-related manufacturing and the return of soldiers led to increased unemployment, less demand, falling prices and crucially, a drop in stock prices.

Clearly, it’s more in-depth, but in terms of health alone this period also saw the world reeling from the outgoing and so-called, Spanish-Flu pandemic. Between 1918 and 1920, it infected an estimated 500-million people worldwide while killing around fifty million. As a result, reports of physical and mental-health disorders relating to the virus and the accompanying stress rose significantly and amongst symptoms, people spoke of depression and sleep disturbances with the spectre of suicide widely prevalent.

By 1922, the situation was changing and like the domino effect, the growing use of cars led to a range of multipliers that included: weather-proof road surfaces, electricity networks along those roads and the growth of suburbs. In those houses, too, were new appliances, lighting and heating as well as telephones and radios: much of which was bought on credit. This technological spread and swollen household debt boosted the economy on so many levels from industry and entertainment to hospitality and healthcare while stock prices climbed, too, as companies revelled in a profit surge. Supporting all of this over time were growing investments in Latin America as well as the war debts of grateful European nations, three of whom the U.S had bankrolled to the tune of some ten-billion dollars.

Of course, not everyone saw prosperity.

Yet, to give some idea of the technologically-fuelled growth between 1919 and ’29, a look at the numbers reveals something staggering. In terms of cars, 6.7 million rose to twenty-three; radios in 19% of half-a-million homes shot up to between 35% and 40%, meaning actual sales of wireless sets jumped from 60 million to 840. Meanwhile, income disparities saw 24% of the national share of disposable income going to the top 5%, in 1920, and rising to 34% of the share, nine years later. The industrial revolution made myriad things possible and the words of the German philosopher and sociologist, Georg Simmel, carried weight:

‘The profound connection between value and exchange, as a result of which they are mutually conditioning, is illustrated by the fact that they are in equal measure the basis of practical life. Even though our life seems to be determined by the mechanism and objectivity of things, we cannot in fact take any step or conceive any thought without endowing the objects with values that direct our activities.’

So, as money started moving through the economy, wages rose, and it would be easy to imagine the relief of a nation as people once again met with increased levels of spending, but it was some of this emerging affluence that made its way onto the New York stock exchange. How? Well, ordinary people desperate for a slice of the pie laid down a portion of the stock price and funded the rest through loans, with the stock itself acting as surety. Now, that – buying on margin – sounds like the definition of insanity but there blinded by greed and endless excitement: investors soon saw their efforts multiply for much of the decade, as growing speculation increased market bubbles. Again, in the words of Georg Simmel:

‘If the object is to remain an economic value, its value must not be raised so greatly that it becomes an absolute. The distance between the self and the object of demand could become so large—through the difficulties of procuring it, through its exorbitant price, through moral or other misgivings that counter the striving after it—that the act of volition does not develop, and the desire is extinguished or becomes only a vague wish. The distance between subject and object that establishes value, at least in the economic sense, has a lower and an upper limit.’

Profound and when the markets infamously crashed in October 1929, the idea of limits was a distant memory to the economic principle of Rational Choice Theory which sees decision-making as logically consistent, when pursuing self-interest. Meanwhile, traders stood on margin owing more than a return on shares could service while a massive run-on-deposits, saw banks failing in the thousands having already lent so much to speculate with.

The short-termism was breath-taking.

A mere 79-years later, in 2008, the world entered its second largest financial crisis and in simplified terms, three areas stood out: Mortgage-Backed Securities, Collateralised Debt Obligations and Credit Default Swaps; also known as derivatives.

MBSs are financial deeds of ownership or bonds with values for trading that are developed as pools of mortgages. They’re similar to Collateralized Debt Obligations, CDOs, which are financial instruments allowing commercial banks to pool together various assets including credit card and corporate debts and differently rated mortgages. From there, they’re sold to investment banks who then offer shares in the resulting packages of cash flow. These, in turn, are sold to investors who receive money to speculate with through the flow of monthly payments made by hundreds of thousands of homeowners. As long as the pooled mortgages are paid and the cash flows, everyone stays happy. Yet, a major caveat held that the mortgages most likely to be paid were packaged as highly valued, triple-A assets through which payment would be immediate, in the event of a default.

This was in contrast to the subprime-mortgage market, normally rated at triple-B or double-B-unrated and where issues of human frailty lay in such high-risk assets being reclassed, more favourably. In fact, a great description of CDOs lies in the excellent film, The Big Short as it recalls the build-up to the financial crash. In a cameo role by Anthony Bourdain, the celebrity chef, he says:

‘Ok, I’m a chef on a Sunday afternoon, setting the menu at a big restaurant. I ordered my fish on Friday, which is the mortgage bond that Michael Burry shorted. But some of the fresh fish doesn’t sell. I don’t know why. Maybe, it just came out Halibut; has the intelligence of a dolphin. So, what am I going to do? Throw all this unsold fish, which is the BBB level of the bond, in the garbage, and take the loss? No way. Being the crafty and morally onerous chef that I am, whatever crappy levels of the bond I don’t sell, I throw into a seafood stew. See. It’s not old fish. It’s a whole new thing! And the best part is, they’re eating 3-day-old, Halibut. THAT, is a CDO.’

Also, at the heart of the impending collapse was something called the credit default swap, CDS. Many investment banks had long since created insurance policies, CDSs, to protect investors against company bankruptcies. A swap is therefore an insurance agreement for a seller, an investment bank to pay a buyer, an investor, in the event of a loan default or bankruptcy of a company. In return, the investor pays a quarterly premium to the investment bank. However, CDSs were soon subject to speculation on the stock market after banks began betting on the failure of various companies. So, in trying to balance the books with a betting win against a pay out, the banks pushed themselves further out on to the ice.

To put that in context, according to accounts recalled in The Guardian newspaper in October of 2008, both Barclays and the Royal Bank of Scotland carried inter-bank, CDS exposure to the tune of 2.4 trillion pounds. Meanwhile, everyone kept stacking CDS bets on the subprime-mortgage market but then the underlying trick lay in the need for defaults to occur sporadically, because if they were to happen across the country all at once: unimaginable fires would burn.

How and why does it come to this, again and again?

Well, it’s a tiny leap in recognising the innate sense of safety that comes with having money, in the bank. Beyond that, for many, growing an income takes on a feeling of status and all that comes with it. Yet, in a 2013 research study, ‘Saving Can Save from Death Anxiety: Mortality Salience and Financial Decision-Making,’ findings on both sides of the Atlantic showed that for some people, the fear of dying is tempered by prudence. The same team then reported on further studies, in 2018, and the message seems to be that money’s enduring power in our ‘practical lives’ as Simmel put it, blinds us to the truth of ourselves.

‘It is not the young people that degenerate; they are not spoiled till those of mature age are already sunk into corruption.’

Montesquieu

Yet, before getting anywhere near death, it’s a reflection of our enduring fear of those intangible health costs, too. The non-material symptoms of grief and pain that come through suffering in conditions that are heart-breaking at best and soul-destroying, at worst.

Back in the mid-noughties, where the clock was still ticking:

The documentary, ‘Inside the Meltdown’ on the PBS news programme, Frontline, explained how by 2007: Bear Stearns, a major U.S investment bank, had bought hundreds of thousands of subprime, high-risk mortgages and turned them into deeds of ownership for trading. At the same time, it had sold hundreds of billions of dollars of CDOs on the global stock market. So, everything needed for a financial and existential crisis was in place, meaning all that remained was for the fuse to be lit.

Turn back the clock, slightly.

In December 2001, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates to below 1.75%, to boost a sluggish economy on the back of the dot.com bubble bursting. You see, during the 90s and in yet another display of human short-termism, investors rushed to speculate on IT start-ups with little to no prospect. As a result, share values rocketed until energy prices, rate rises and 9/11, shattered the illusion. As production slumped, unemployment rose and with less consumer spending after the terrorist attacks, some form of economic stimulation was needed.

So, until September 2004, the federal reserve kept rates below 1.75% but from here on they would rise until June 2006, when they hit 5.25%. Yes, what happened in between finally lit the touch paper. Low rates had encouraged an increase in loan applications and as the demand for mortgages grew, house prices rose. That subsequent bubble mushroomed until the rate rise, blew it wide open. Suddenly, people could no longer afford repayments which in turn dried up the cash flow packages making MBSs, CDOs and CDSs more or less worthless, in a relatively short space of time. Joe Nocera, still of The New York Times, expressed the notion of short-termism:

‘Accelerating house prices created a mentality amongst everybody involved in the mortgage industry, from the buyer of the house to the mortgage broker, to the bank to Wall Street; that housing prices could only go up.’

Indeed, as Jean-Paul Sartre said: freedom can be overwhelming.

‘If many a man did not feel obliged to repeat what is untrue, because he has said it once, the world would have been quite different.‘

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

So, Bear Stearns, alongside other major investment banks and insurance companies carried too much high-risk debt and as the housing bubble burst, the securities and obligations became worthless. Well, Armageddon loomed as investors panicked with the realisation that everyone was trying to dump the derivatives that no-one else wanted to buy.

In some respects: it was 1929, all over again.

The critical difference now was that the domino effect was instantaneous due to modern technology and the entangled indebtedness of corporate America: particularly through speculation on CDSs and CDOs. So, at first, Ben Bernanke, the then chairman of the Federal Reserve instigated a plan to bail out Bear Stearns whose exposure to ‘toxic assets,’ ran into billions. This was systemic risk 101, and it meant stocks and bonds devalued in a heartbeat as panic spread like a forest fire through the American financial system, before hitting global stock markets. When the bank still failed, Lehman Brothers were next on the block but any assumption of a rescue was killed off by the idea of ‘moral hazard.’ Hank Poulson, the then United States Secretary of the Treasury felt deliverance gave no incentive for future caution whilst at the same time noting: they had “very little time, in which to solve this.”

‘Everything freezes and that’s what causes the crisis, and it really started because Lehman Brothers went into bankruptcy. No-one, forecast that this was going to happen, but it turns out that this one decision made all the difference.‘

Charles Duhigg, formerly of The New York Times

‘Everybody said: “My God, we may be presiding over the second great depression.“

So said, Paul Krugman, an eminent economist formerly of Princeton University and in fact as in the 1920’s, people’s hunger for fast money convinced them that a seemingly good thing was limitless. It remains the problem in need of addressing. How do you change a fundamental aspect of human nature? Mike Petrucelli, a former Senior VP at Lehman Brothers said:

‘I think in hindsight it’s easy to see that there was a bubble, but you know, sometimes when you’re at a party and having a good time: it’s hard to stop and leave the party.’

It’s hard to argue with that but not the subsequent issue of the general public, who’d had nothing to do with toxic securities but were asked or rather told to pay for the shindig. That offensive stench traversed the Atlantic to annoy Europeans and others, too, as the contagion spread globally. So, the basic question, it seems, has always been: how do you align long-term planning with the reality of short-term desires? The question is absurd, philosophically and tangibly, and so the answer maybe lies not in trying to change human nature but in once again, looking at the system. Of course, this has long been recognised in anti-capitalist thinking, but then capitalism drives innovation and progress by virtue of its willingness to reward hard work. Therein lies the issue for too many. Hard graft drives progress and reward as consumption ignores the needs of others that are sometimes desperate. So, enters socialism which in some guises, seeks to promote equality for all.

Yet, the competition for resources by its very nature, distils the idea of balanced citizenship in terms of reward, not rights, because some are naturally inclined to work harder than others and often regardless of incentive. It all seems like a bit of a mess, and the system remains unconcerned that people’s short-term habits that are clearly grist to the mill in driving the free market and its crises: are paradoxical. Still, the nature of all that is a subject for scholars.

It’ll happen again, Brooksley Born outlined in the documentary, ‘The Warning’. The former Head of the U.S Commodity Futures Trading Commission, said:

‘I think we will have continuing danger from these markets, and we will have repeats of the financial crisis: maybe different details, but there will be significant financial downturns and disasters attributed to this [derivatives] regulatory gap over and over, until we learn from experience.’

Astonishingly, those words were uttered a few years before the 2008 crash. Why? Because between 1996 and ’99, she tried to warn of the systemic risk posed by derivatives and made attempts to regulate the market but was fought, tooth and nail by the chairman of the Federal Reserve; the Secretary of the Treasury; the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission and Congress, itself. Soon afterwards, the hedge fund, Long-term Capital Management almost failed due its deep exposure but the U.S government ordered Wall Street to bail it out and it was seen, as a one-off event. In the end, Brooksley Born was silenced as the CFTC was defanged, so to speak, and she resigned.

In the documentary, Arthur Levitt, the former SEC chairman expresses deep regret over the way she was treated.

‘I’ve come to know her as one of the most capable, dedicated, intelligent and committed public servants that I have ever come to know. I wish I knew her better in Washington. I could have done much better. I could have made a difference.’

Short-termism, continues to be breathtaking and it states the obvious, too. If the masters of finance can’t resist the cliff edge no matter how many times they go over it: how can the long-term future of the planet register?

It’s a series of crises within the biggest existential crisis of all and we can all in truth, only hope.

Copyright © 2023 | recoveryourwellbeing.com | All Rights Reserved

Images:

Counting Coins, by Frantisek Krejci, Pixabay – Main Image

Remembering the War Dead, by Hub Jacqu, Pexels

Boys in Poverty, by Flutie, Pixabay

Roaring Twenties, Fifties and Hundreds, by Gera Cejas, Pexels

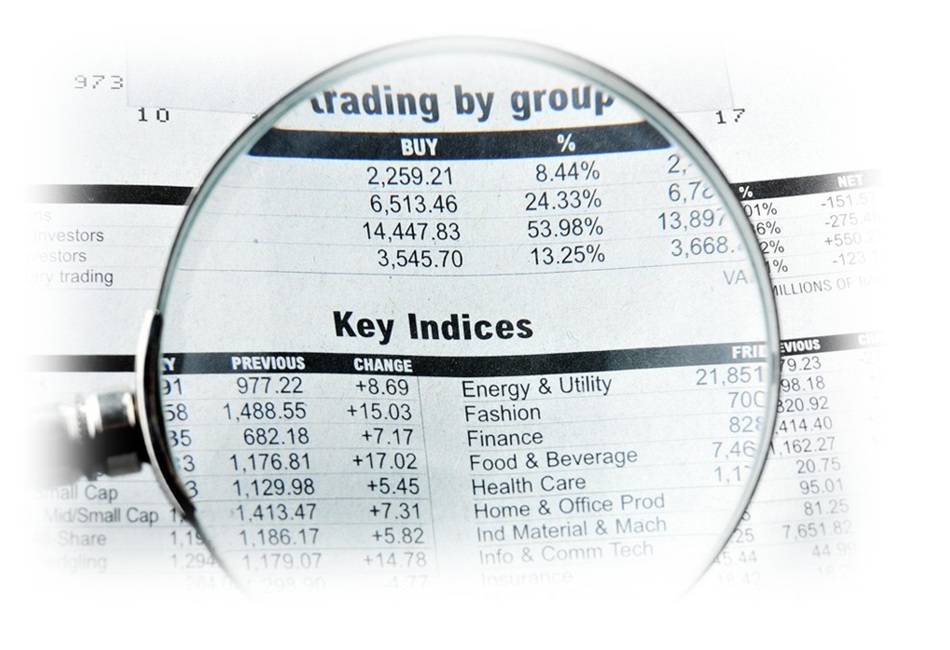

Magnified Indices, by AbsolutVision, Pixabay

Greedy Pig, by Deez Nutz, Pixabay

New York Stock Exchange, by David Hou, Pexels

References:

Ferreria MJ. ‘Faith and the Kierkegaardian Leap’, In: Hannay A, Marino GD, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard. Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997:207-234. Doi:10.1017/CCOL0521471516.009 https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/cambridge-companion-to-kierkegaard/faith-and-the-kierkegaardian-leap/4DD1934FA98676CE165BAA20DB59E2CA

Quote Investigator, ‘The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, and expecting different results’, 23rd March 2017, accessed 12th December 2023, https://quoteinvestigator.com/2017/03/23/same/

Imperial War Museum, ‘Timeline of 20th and 21st Century Wars’, 2023, accessed 11th December 2023, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/timeline-of-20th-and-21st-century-wars#:~:text=Conflict%20took%20place%20in%20every,from%201900%20to%20the%20present

Zbigniew Brzezinski, ‘Out of Control: Global Turmoil on the Eve of the Twenty-first Century (New York, Harper Collins Publisher, 1994) https://books.google.es/books/about/Out_of_Control.html?id=FzZnAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y

Harold Evans, ‘The American Century’ (New York, Knopf, 1998) 1st Edition, https://books.google.es/books/about/The_American_Century.html?id=a013AAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y

BER Staff, ‘In The Shadow of the Slump: The Depression of 1920-1921’, Berkley Economic Review, Para 4, 18th March 2021, accessed 12th December 2023, https://econreview.berkeley.edu/in-the-shadow-of-the-slump-the-depression-of-1920-1921/

Haelim Anderson and Jim-Wook Chan, ‘Labour Market Tightness During WWI and the Post-war Recession of 1920-1921’, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2022-049, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, pp2, para 3, accessed 12th December 2023, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2022-049

Greg Eghigian, ‘The Spanish Flu Pandemic and Mental Health: A Historical Perspective’, Psychiatric Times, 28th May 2020, Vol 37, Issue 5, Paras 1, 4 & 5, accessed 12th December 2023, https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/spanish-flu-pandemic-and-mental-health-historical-perspective

Gene Smiley, ‘The U.S Economy in the 1920s’, Economic History Association, E.H Net Encyclopedia, Edited by Robert Whaples, Para 1, 29th June 2004, accessed 12th December 2023, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-u-s-economy-in-the-1920s/

John Stepek, ‘How America’s Roaring ‘20s Paved The Way for the Great Depression’, Moneyweek, 10th November 2017, Para 18, accessed 13th December 2023, https://moneyweek.com/476326/how-americas-roaring-20s-paved-the-way-for-the-great-depression

Carlos Lozada, ‘The Economics of World War I’, National Bureau of Economic Research, Issue No.1, January 2005, Para 6, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.nber.org/digest/jan05/economics-world-war-i

Editorial, ‘An Economic Superpower: How the Great War Turned America Into an Economic Superpower’, American Experience, 2023, Para 8, accessed on 13th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/the-great-war-economic-superpower

Steven Mintz, ‘Statistics: The American Economy During the 1920s’, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, 2023, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/teaching-resource/statistics-american-economy-during-1920s

George Simmel, ‘The Philosophy of Money’ (Oxfordshire, Routledge, 2004) 3rd Edition, pp81, https://www.amazon.co.uk/Philosophy-Money-Georg-Simmel-ebook/dp/B000OT89L4/ref=sr_1_3?crid=2UXL9N6FPQGXW&keywords=the+philosophy+of+money&qid=1702840898&sprefix=%2Caps%2C81&sr=8-3

Gary Richardson, et al, ‘Stock Market Crash of 1929’, Federal Reserve History, 22nd November 2013, Para 3, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/stock-market-crash-of-1929

Cliff Notes, ‘The Beginnings of the Great Depression’, U.S History II, 2023, https://www.cliffsnotes.com/study-guides/history/us-history-ii/depression-and-the-new-deal/the-beginnings-of-the-great-depression

James Chen, ‘Buying on Margin: How It’s Done, Risks and Rewards’, Investopedia, 21st April 2021, Para 23, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/buying-on-margin.asp

George Simmel, ‘The Philosophy of Money’ (Oxfordshire, Routledge, 2004) 3rd Edition, pp69, https://www.amazon.co.uk/Philosophy-Money-Georg-Simmel-ebook/dp/B000OT89L4/ref=sr_1_3?crid=2UXL9N6FPQGXW&keywords=the+philosophy+of+money&qid=1702840898&sprefix=%2Caps%2C81&sr=8-3

Herbert Hoover, Presidential Library and Museum, ‘1929’, National Archives, 2023, accessed 13th December 2023, https://hoover.archives.gov/exhibits/great-depression

Catherine Herfield, ‘Revisiting Criticisms of Rational Choice Theories’, Wiley Online, Philosophy Compass, 21st December 2021, accessed 13th December 2023, doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12774, https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/phc3.12774

Official Website of the United States Government, ‘The Depression’, Social Security History, 2023, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.ssa.gov/history/bank.html

Julia Kagan, ‘Mortgage-backed Securities (MBS) Definition: Types of Investment’, Investopedia, 19th October 2023, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/mbs.asp

Carla Tardi, ‘Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDOs): What It Is; How It Works’, Investopedia, 21st April 2023, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/cdo.asp

U.S Department of Justice, ‘Goldman Sachs Agrees to Pay More Than $5 Billion in Connection With its Sale of Residential Mortgage Backed Securities’, Office of Public Affairs, Para 2, 11th April 2016, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/goldman-sachs-agrees-pay-more-5-billion-connection-its-sale-residential-mortgage-backed

‘The Big Short’, Paramount Pictures, et al, 22nd January 2016, IMDb, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1596363/

‘The Big Short, Anthony Bourdain Explains CDOs’, 2019, ‘Calvin Lim’, Youtube, accessed 14th December 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kxN_qPuefrM

Adam Hayes, ‘What Is a Credit Default Swap and How Does It Work?’ Investopedia, 12th August 2023, accessed 13th December 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/creditdefaultswap.asp

Amanda Cooper, ‘Explainer: What Are Credit Default Swaps and Why Are They Causing Trouble for Europe’s Banks?’ Reuters News Agency, 30th March 2023, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.reuters.com/markets/what-are-credit-default-swaps-why-are-they-causing-trouble-europes-banks-2023-03-28/

Simon Bowers, ‘Derivatives Worth Hundreds of Millions of Dollars Start to Unwind’, The Guardian Newspaper, 11th October 2008, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/oct/11/lehmanbrothers-royalbankofscotlandgroup

Tomasz Zaleskiewicz, et al, ‘Saving Can Save from Death Anxiety: Mortality Salience and Financial Decision-Making’, PloS ONE 8(11):e79407, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079407, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258639355_Saving_Can_Save_from_Death_Anxiety_Mortality_Salience_and_Financial_Decision-Making

Agata Gasiorowska, et al, ‘Money as an Existential Anxiety Buffer: Exposure to Money Prevents Mortality reminders from Leading to Increased Death Thoughts’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79(5):394-409, doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2018.09.004, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327883091_Money_as_an_existential_anxiety_buffer_Exposure_to_money_prevents_mortality_reminders_from_leading_to_increased_death_thoughts

Montesquieu Quote – ‘It is not the young…’, Brainy Quote, 2023, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/montesquieu_390655?src=t_corruption

‘Cost of Illness’, Science Direct, Bone Cancer (Second Edition) 2015, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/cost-of-illness

‘Inside The Meltdown’, PBS, Frontline, 17th February 2009, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/meltdown/

Editorial, ‘Fed Cuts Rates a Quarter Point’, CNN Money, Para 2, 11th December 2001, accessed 14th December 2023, https://money.cnn.com/2001/12/11/economy/fed/

Editorial, ‘The Late 1990s Dot-Com Bubble Implodes in 2000’, Golman Sachs, Paras 3 & 4, 2019, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.goldmansachs.com/our-firm/history/moments/2000-dot-com-bubble.html

Editorial, ‘Fed Cuts Rates a Quarter Point’, CNN Money, Para 14, 11th December 2001, accessed 14th December 2023, https://money.cnn.com/2001/12/11/economy/fed/

Editorial, ‘Federal Reserve Raises Interest Rates by Quarter-point – Business – International Herald Tribune, The New York Times, Para 2, 29th June 2006, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/29/business/worldbusiness/29iht-web.0629fed.2083321.html

Editorial, ‘Federal Reserve Raises Interest Rates by Quarter-point – Business – International Herald Tribune, The New York Times, Para 5, 29th June 2006, accessed 14th December 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/06/29/business/worldbusiness/29iht-web.0629fed.2083321.html

Jon Ogg, ‘CDOs and the Mortgage Market’, Investopedia, Para 28, 20th July 2023, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/07/cdo-mortgages.asp

Joe Nocera, ‘Quote’, Inside the Meltdown, transcript, PBS Frontline Documentary, 17th February 2009, 6m:55s, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/meltdown/etc/script.html

‘The Maxims and Reflections of Goethe’, Translated by Thomas Bailey Saunders, 1908, Digitised by Google, Page 196, Maxim No: 564, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.google.es/books/edition/The_Maxims_and_Reflections_of_Goethe/XZg9AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=the+maxims+and+reflections+of+goethe&printsec=frontcover

Jill Treanor, ‘Toxic Shock: How The Banking Industry Created a Global Crisis’, The Guardian newspaper, 8th April 2008, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/apr/08/creditcrunch.banking

Governor Kevin Warsh, ‘The Panic of 2008’ Speech Transcript, Para 5, Federal Reserve Board of Governors, At the Council of Institutional Investors 2009 Spring Meeting, Washington D.C, 6th April 2009, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/warsh20090406a.htm

Gilbert Geis, ‘How Greed Started The Dominoes Falling: The Great American Economic Meltdown (Part 1 of 2)’, Fraud Magazine, Nov/Dec 2009, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.fraud-magazine.com/article.aspx?id=641

James Langton, ‘S&P Moves Bear Stearns Outlook to Negative’, Investment Executive, Para 3, 3rd August 2007, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-inside-the-meltdown/

Jenny Anderson and Vikas Bajaj, ‘A Wall Street Domino Theory’, The New York Times, 15th March 2008, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/15/business/15risk.html

Heidi N. Moore, ‘Lehman Brothers, Moral Hazard and Who’s Next?’, The Wall Street Journal, 14th September 2008, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-DLB-3419

Charles Duhigg, ‘Quote’, Inside The Meltdown, PBS Frontline Documentary, Season 2009, Episode 4, 35m:56s, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-inside-the-meltdown/

Paul Krugman, ‘Quote’, Inside The Meltdown, PBS Frontline Documentary, Season 2009, Episode 4, 36m:22s, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-inside-the-meltdown/

Michael Petrucelli, ‘Quote’, Inside The Meltdown, PBS Frontline Documentary, Season 2009, Episode 4, 28m:32s, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-inside-the-meltdown/

Charles McDaniels, ‘Review of Intellectuals and Money’ by Alan S. Kahan, The Review of Politics 72, No.4, (2010): 753-55, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40961162

Will Kenton, ‘Socialism: History, Theory and Analysis’, Investopedia, Behavioural Economics, 1st July 2023, accessed 17th December 2023, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/socialism.asp

The Warning, PBS Frontline Documentary, Season 2009, Episode 14, 22m:45s, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-the-warning/

Franklin R. Edward, ‘Hedge Funds and the Collapse of Long-Term Capital Management’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 13, No.2, Spring 1999, pp189-210, accessed 16th December 2023, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.13.2.189

Arthur Levitt ‘Quote’ The Warning, PBS Frontline Documentary, Season 2009, Episode 14, 48m:01s, accessed 15th December 2023, https://www.pbs.org/video/frontline-the-warning/